This article is a bit different from the others in the portfolio. It’s dedicated to my friends and colleagues who asked me about the strange-looking keyboard on my desk. Maybe I can pique your interest in exploring the world of ergonomic custom keyboards with me.

General Idea

Many people spend large parts of their waking hours with their hands on a keyboard, notably computer professionals like programmers. Because the traditional QWERTY keyboard was not designed with ergonomics or typing speed in mind, people began developing alternative designs.

Physical Layout

The first idea is to arrange the keys according to the fingers. Since

the fingers move vertically, the keys on ergonomic keyboards are

arranged in columns, with each column corresponding to one finger. Using

fewer physical keys reduces the travel distance of each finger, with

most fingers only ever touching three different keys (except the thumb

and index finger, which touch two and six, respectively). This is

achieved through layers. You are already familiar with layers

since traditional keyboards have a Shift key that, when

held down, changes the character displayed. Most notably, it provides

the capital version of a letter, or a symbol instead of a number. The

idea is to have additional layers that can be accessed by holding down

one of the thumb keys. This way, numbers, navigation keys, and symbols

don’t need their own dedicated physical key.

Another benefit to a physical layout matching the human hand is that hitting the wrong key is much less common. I never have to move my whole hand and the maximum distance my finger has to move is one key, mostly just straight up or straight down (with the exception of the index finger, which also goes sideways sometimes). In practice, this higher accuracy also translates to increased typing speed.

Logical Layout

The next design challenge is to create a good mapping between the inputs (e.g., letters and symbols) and the physical keys. This is freely configurable and I’ll show you what works for me as a someone who writes mostly code, English text, and German text.

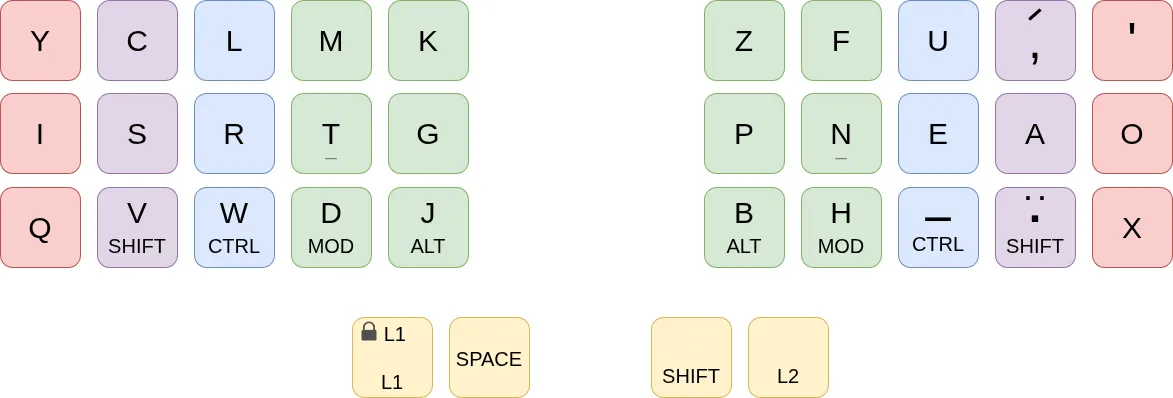

As with the traditional keyboard, the lowercase letters, comma, and

period are the primary keys and make up the main layer, which is also

called the base layer or L0. Since I write code in Python frequently, I

also added the underscore as a regular key for quick access. Otherwise,

the layout I’m using here is known as the “ISRT” layout and is one of

hundreds of computer-optimized alternatives to QWERTY.

Ideally, the most frequently used letters are easily reachable. In

English, E, T, A, O,

I, N, S, and R are

often considered the most common letters, and together, they make up

about 60% of all letters in text. Since these letters correspond to the

keys my fingers rest on, I don’t need to move away my fingers at all for

many keystrokes. Conveniently, many other languages, such as German,

share most of these eight most common letters.

Furthermore, letters that commonly occur in sequence (e.g.,

T and H) are placed so that they are not

pressed by the same finger, improving speed and comfort.

Finally, holding down a key instead of tapping it can reveal

different functionality. For example, holding down the W

key does not type “w”; instead, it acts like holding down the

Ctrl key. This way, the keys that need to be held down are

much closer to where the fingers are, so there is less strain on the

wrist and pinky finger than with traditional keyboards.

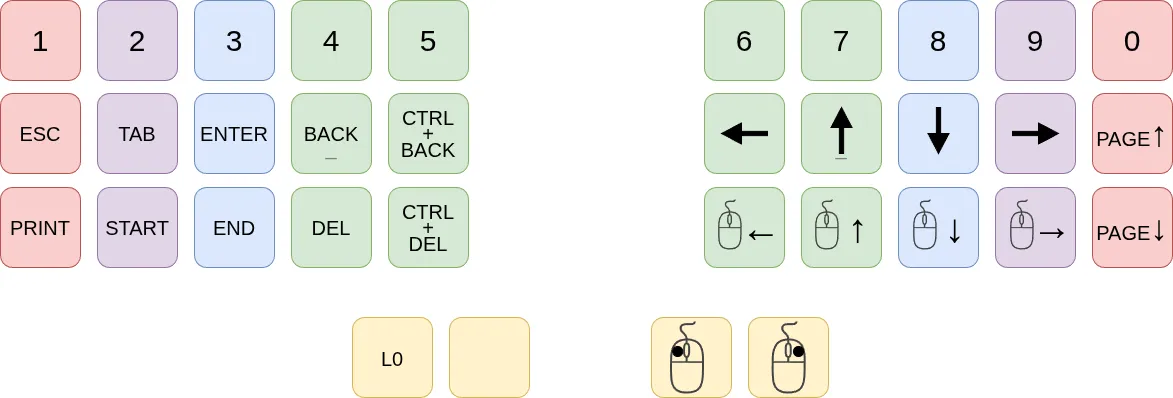

The navigation layer is probably my second most used layer. It is

accessed by holding down the leftmost thumb key. Besides numbers, it

contains all the keys needed to navigate text. The more commonly used

keys, such as Enter and Backspace, are located

in the center, while the less commonly used keys, such as

Print Screen, are located on the edges.

I can also move the cursor and do clicks through key presses, which works surprisingly well due to the cursor acceleration that reacts to how long I’m holding down the respective mouse movement key. A regular mouse still works better, of course, but it’s nice to have a backup.

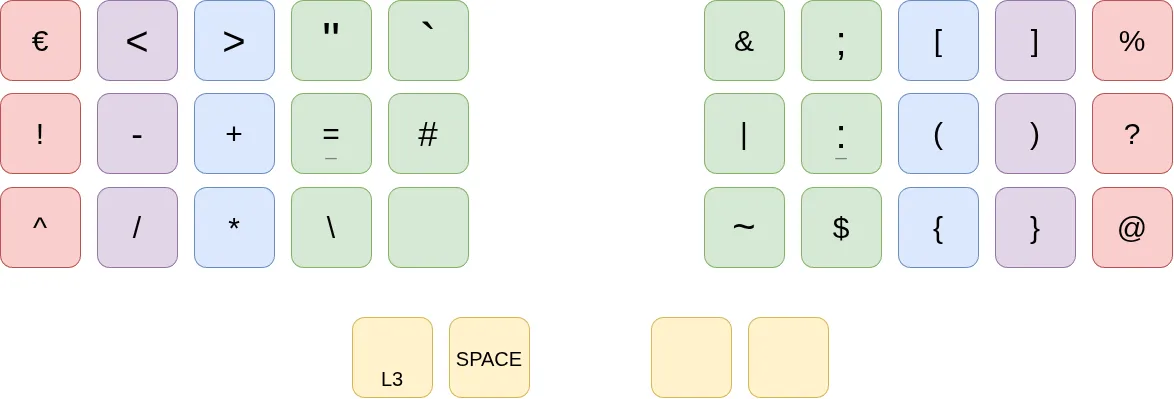

The symbol layer, adapted from Pascal Getreuer’s ideas, prioritizes

common code patterns, such as +=, -=,

!=, ${}, /*, */

->, and =>, ensuring that they are not

pressed with the same finger. It also places frequently used symbols,

such as =, -, and (), in the

center. In contrast, keys that are less conveniently reachable, such as

those in the corners where you need to move your pinky or move your

index finger diagonally, are assigned to more rare inputs, such as the

symbols ^ and ~.

The Shift layer, accessed by holding down the third thumb key, is not

shown here, but it unsurprisingly contains capitalized letters. An

additional perk is that when I press Shift and period then

the next letter pressed will be the “German version”, e.g., “ä” instead

of “a” or “ß” instead of “s”. Pressing Shift and comma

turns the next press into “Spanish mode”, with “á” instead of “a” and

“ñ” instead of “n.” If you primarily type in languages other than

English, you may want to use a more accessible combination, for example

switching to your language-specific layer by holding down the thumb key

that is currently Space when tapped or by replacing what

are now the cursor movement keys with, e.g., ä,

ö, ü, and ß.

I have an additional layer L3 containing the keys F1

through F12 and the volume control keys, but I rarely use

them.

Closing Remarks

I hope you found this overview interesting. There is a lot more to talk about and I’m happy to do so in person.

FAQ

How was the transition from a traditional keyboard?

I personally practiced the new layout for about two weeks for half an hour per day before switching completely. For practice, I used MonkeyType with custom word lists, starting with words that only contain the most common letters, then slowly expanding to more letters. After a week of switching I was typing fast enough to not feel like I’m being held back by the less familiar new layout anymore and after less than a year I was already considerably faster than I had been with my old keyboard.What switches are you using?

I have one keyboard with “Outemu Silent Lemon v3” and another one using “Gazzew Boba U4 silent”, both of which are tactile and both are silent switches, which makes them suitable for shared office environments. I like both, however, the latter need to be pressed harder, which is why my first thumb (which I hold down often) key uses a lighter linear switch.How can I get an alternative keyboard layout to work with Vim and similar programs?

basically you reassignH,J,K,Lin normal mode toP,N,E,A. In Vim with e.g. “nnoremap p h”. There are some more caveats, but I’m happy to help. In other programs like LF or neomutt, you just assign those 8 letters to specific actions. The other letters that are not on the right home row, I mostly kept, i.e.ufor undo in Vim. For the beginning, you can usually just use the arrow keys until you updated all you programs’ configs.What about wireless keyboards?

There are wireless versions of most such keyboard models, but they are slightly more complicated to set up and maintain, e.g., you have to recharge them regularly. I personally find wired keyboards more practical and I don’t mind the cable “clutter” on my desk, since I almost never look down while I’m on the computer.Why does the traditional keyboard look the way it does?

The short answer is: It is based on the type writer (which itself is based on the piano). Meanwhile, the typewriter had certain mechanical limitations. Finally, there is an impressive degree of societal inertia. The long answer has been thoroughly discussed in places like YouTube.Where can I find more resources on the topic?

There is a reddit community dedicated to this, eventhough a lot of the content is just people sharing pictures of their hardware. Also there are some youtubers known for making videos about the topic, e.g. Ben Vallack, who experimented with keyboards that have fewer than 20 physical keys. I recommend checking out the blogger Pascal Getreuer, who discusses some aspects of this topic in more depth.